THE BREUER BUILDING, 945 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, September 13, 2023 – Over the course of the last century or so, a small number of individuals have played a vital role in shaping the unfolding story of 20th century art. Emily Fisher Landau was a key member of this group: her deep and longstanding involvement with leading institutions, in particular as a working member of the Whitney Museum of American Art board for thirty years; her profound engagement with the art and artists of her time and her unerring instinct as a collector at the highest level, all combined in one of the greatest collectors and patrons of the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s.

Though her interest in art began in childhood, her passion for collecting began in in the late 1960s with the purchase of a striking Alexander Calder mobile (which, in spite of its size, she determinedly carried home single-handedly on a cross town bus) and with a chance encounter with a poster advertising a forthcoming Josef Albers show. Immediately struck by the power of this minimal image, she visited the exhibition and three major acquisitions soon followed.

Shortly afterwards, an unexpected event provided a rapid spur to her newfound desire for collecting. The theft from her home of her many magnificent jewels resulted in a substantial insurance payment which she decided she would prefer to use to finance her adventures in art. The die was cast.

Now collecting in earnest, Mrs. Fisher Landau began to put together a major ensemble of works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Jean Arp, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Paul Klee and Louise Nevelson among others. All were complemented, in later years, by the work of artists Mrs. Fisher Landau came to know and patronize directly, many of whom she collected in depth.

This Fall, following a series of international exhibitions that will allow audiences around the world to see for the first time the extraordinary range and quality of Mrs. Fisher Landau’s collection, some 120 exceptional works from the collection, estimated to bring well over $400 million, will be offered for sale at Sotheby’s New York in two dedicated auctions, on 8th and 9th November, which are destined to be a historic moment for the art market.

EMILY FISHER LANDAU

LIFE AND LEGACY

Pierre Hotel in New York in 1970

Born in 1920 and raised in Upper Manhattan, Emily Fisher Landau loved art right from the outset. Her own artistic talents were evident from an early age but, though she was accepted into art school, she was unable to attend because of the Depression. Her instinctive love of art remained, however, undimmed. In the 1960s, with the encouragement of her husband Martin Fisher, she took her first informal steps into the world of collecting.

It all began in 1968, with the purchase of the Alexander Calder mobile mentioned above – a work which, with typical ingenuity and flair, she later hung over her bathtub. This was followed soon after by the ‘light bulb’ moment when she first saw the work of Josef Albers at Pace Gallery in New York (“From the minute I saw that Albers, I knew I loved simplicity.”), and the start of a lasting friendship with the gallery’s owner Arne Glimcher. It is from them that Mrs. Fisher Landau made her first major acquisitions – a trio of masterworks by Picasso, Léger and Dubuffet.

Armed with this substantial insurance pay out, Mrs. Fisher Landau set about swiftly replacing her jewels with art, acquiring major works by Modern masters Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee and others. At the same time, through Glimcher, Mrs. Fisher Landau was introduced to the vibrant New York art scene of the moment. Through him, she met Ed Ruscha, Jasper Johns, Mark Rothko, Andy Warhol and other prominent artists of their time – visiting their studios, engaging with their lives and work, and acquiring, as they were created, those pieces that spoke strongest to her intuitive eye.

But then in 1976, Martin Fisher died. The love of Emily Fisher Landau’s life, he had supported her in her collecting as in everything (colorblind, he kept a crib sheet of their paintings in his pocket so as to better appreciate and converse about them). Her collecting stopped, and it was not until 1981, soon after her marriage to Sheldon Landau, when she met designer Bill Katz, that it was to be rekindled, taking, this time, a slightly different direction.

Mrs. Fisher Landau now began to engage again, this time yet more deeply, with contemporary artists. She visited artists’ studios and galleries, and built strong, lasting friendships with a host of artists – Georgia O’Keeffe, Agnes Martin, Keith Haring, Robert Rauschenberg, Louise Nevelson, Cy Twombly, Glenn Ligon, Nan Goldin, Mark Tansey, Robert Mapplethorpe and many others.

In all of this, Mrs. Fisher Landau cared deeply, not just about the art, but about the artists too. She collected their work in extraordinary depth – sometimes buying out whole shows, sometimes buying one standout work, but always returning for more.

In all of this, Mrs. Fisher Landau cared deeply, not just about the art, but about the artists too. She collected their work in extraordinary depth – sometimes buying out whole shows, sometimes buying one standout work, but always returning for more.

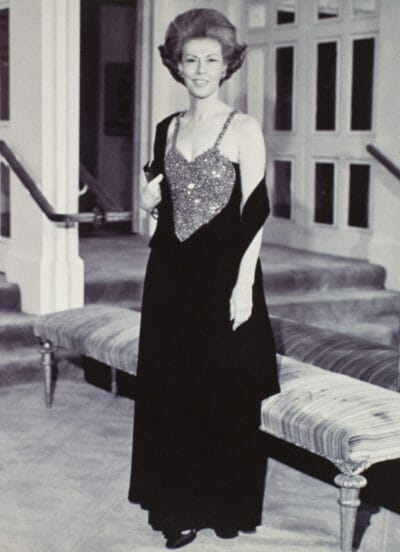

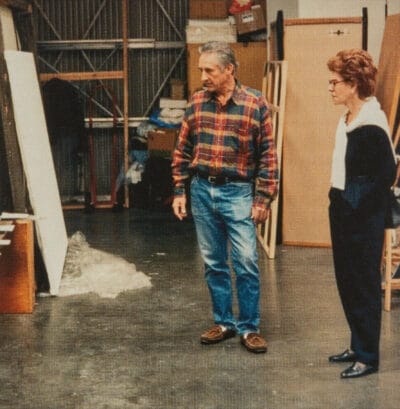

Mrs. Fisher Landau with Ed Ruscha at the Whitney Museum in 2013. Photo by Craig Barritt / Getty Images; Mrs. Fisher Landau with Jasper Johns on her 90th birthday at the Whitney Museum in 2010. Photo by Nick Hunt/ Patrick McMullan via Getty Images

EMILY FISHER LANDAU

A CHAMPION OF AMERICA’S GREAT INSTITUTIONS

Photo by Matthew Roberts

Mrs. Fisher Landau’s adventurous spirit and total commitment to the art and artists of her time was, as it happened, in perfect step with the approach and ethos of the increasingly influential Whitney Museum, then housed in the Breuer building on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. As she herself expressed it:

From the mid-1980s, when she was appointed a trustee, her relationship with the museum became ever closer. Over the next three decades, she was deeply involved with the Whitney in so many ways, including chairing the Painting and Sculpture Acquisition Committee. A fierce champion of progressive American artists, she supported them by endowing the Whitney Biennial exhibitions. In 2010, her life’s work and association with the Whitney was cemented, with an unprecedented donation of nearly 400 works subsequently exhibited under the title “Legacy: The Emily Fisher Landau Collection”. The fourth floor of the Breuer building remains named in her honor.

She also sat on committees at the Museum of Modern Art and on the boards of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and SITE Santa Fe. In parallel with all of this, Mrs. Fisher Landau also established her own Fisher Landau Center for Art in Long Island City. Needing to find a suitable space to house her immense collection, in the late 1980s she purchased a former parachute harness factory. Reconfigured by Max Gordon, this was soon to become a fully-fledged art center where her collection could be shared with the public.

A GLIMPSE INSIDE THE COLLECTION

PICASSO

Mrs. Fisher Landau bought this painting in 1968, right at the start of her collecting journey. This major acquisition was a bold move for a new collector, but she understood full well that it was not the sort of work she should pass up: she bought it on the spot, and it remained the keystone of her collection for more than five decades, hanging above the mantle in her New York home.

The painting’s importance within Mrs. Fisher Landau’s heart and home is more than matched by its significance within Picasso’s oeuvre: depicting Marie-Thérèse Walter, the artist’s ‘golden muse’ and the subject of many of his most accomplished portraits, it dates from 1932, a year of such importance that an entire museum exhibition was dedicated to it (Tate Modern, 2018). Of the many great paintings, though, that Picasso created in 1932, this one in particular stands out.

It was painted in August, soon after the close of his first, large-scale retrospective at the Galeries Georges Petit in Paris, at a moment when – finally free from the stresses of the exhibition and the strain of secrecy around his clandestine affair with Marie-Thérèse – he was able to give full painterly voice to his love for her.

Picasso’s first encounter with his young muse, and their subsequent love affair, is legendary. They first met outside the Galeries Lafayette in Paris one day in 1927, a brief exchange marking the start of a passionate relationship that was kept a well-guarded secret for years, both on account of the fact that Picasso was then still married to Russian-Ukrainian dancer Olga Khokhlova, and because of Marie-Thérèse’s young age (she was just seventeen when they met).

As time passed, Picasso found it ever harder to exclude his lover’s features from his art, and when the retrospective of his work opened in June 1932, there could be absolutely no doubt as to who reigned – on canvas as in his affections. The truth was out, and Picasso’s marriage with Olga was over.

Though this was certainly a tumultuous time for Picasso, the great success of the exhibition and the sense of release from keeping secrets about his affair seem to have spilled out onto this extraordinary canvas, in which he gives full painterly rein to new-found freedoms, drenching the painting in strong primary colors and beautiful forms, while at the same time paying careful attention to every small detail, creating a composition that is both intensely complex and deeply harmonious.

In so many ways, the Fisher Landau Picasso ranks as one of the artist’s pre-eminent works: its date, scale, subject, vibrancy and provenance are all exceptional, and perfectly aligned. But in addition to this, it has another important distinguishing feature: the watch that the artist has so conspicuously placed on Marie-Thérèse’s wrist.

Among the many paintings Picasso created in his long and varied career, only three major works, including this, are known to feature a watch, yet watches were objects of immense significance to him, in various ways. Picasso had a deep passion for exceptional timepieces, and in fact owned three of the greatest watches in existence. To depict his young lover wearing one of his treasured watches was therefore to bestow on her the greatest of honors – a gesture not lost on Marie-Thérèse, who had ‘an almost superstitious reverence’ for the watch. At the same time, the presence of the watch nods to the centuries-old tradition of Vanitas painting, with its references to the transience of both love and life.

Even more than this, the watch speaks to Picasso’s deep preoccupation with broader concepts of time and space and with the practicalities of defining and measuring time. In fact, just as Albert Einstein was grappling with those same intellectual concepts, Picasso was exploring new ways to express them in paint. And so, in addition to its symbolic importance, the prominence of the wristwatch here also reflects Picasso’s full engagement with what was a crucial moment in European intellectual history.

No other 1932 Picasso of remotely similar importance has appeared on the auction market since 2010, when Nude, Green Leaves and Bust from the estate of Mrs. Sidney F. Brody established a new record price for any work of art ever sold at auction.

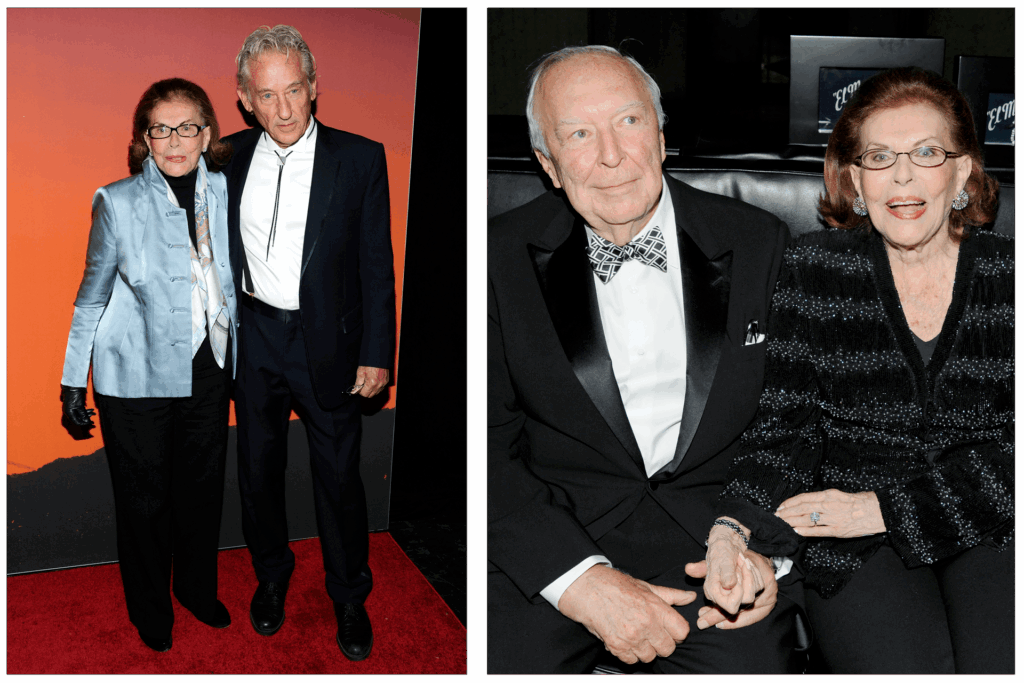

RUSCHA

1964, oil on canvas, 59 x 55 inches

Estimate on request

Mrs. Fisher Landau was Ed Ruscha’s staunchest supporter, visiting the artist several times in his studio in Los Angeles and assembling an unparalleled collection of the artist’s works. Though she embraced his full output, she was particularly drawn – perhaps as a result of her own dyslexia – to his revolutionary text paintings, a theme that runs throughout her collection.

Ed Ruscha is one of the key figures who define post-war American art, his iconic output of the 1960s in particular capturing the moment when mass media and advertising began to exert a pull, not only over consumers, but artists too.

Of the many types of works he has produced in his long career, Ruscha’s ground-breaking text paintings stand out. Novel, bold and arresting, they catapulted Ruscha to the forefront of American art of the 1960s, capturing a moment when the power of the word was being felt in new and unexpected ways – splashed boldly across posters and TV advertisements – and blurring the lines between language and visual art. Just as Warhol elevated everyday objects in his works, here Ruscha extracts commonplace words from their mundane contexts, elevating them and making them a grand yet subversive subject in their own right.

A masterpiece from a small group of large-scale text paintings of this type, Securing the Last Letter (Boss) develops on a work produced three years earlier, now hanging in the Broad Museum in Los Angeles. Here, Ruscha takes that 1961 image one powerful, playful step further, introducing a utilitarian c-clamp which squeezes into the bubbly glamor of the final ‘S’ with brilliant trompe l’oeil effect.

Having featured in numerous key exhibitions, including at the Whitney Museum in New York and the Hayward Gallery in London, Ruscha’s Securing the Last Letter (Boss) is among the greatest of the artist’s works ever to come to the market.

CA in 1985. Image courtesy Emily Fisher Landau Center for Arts

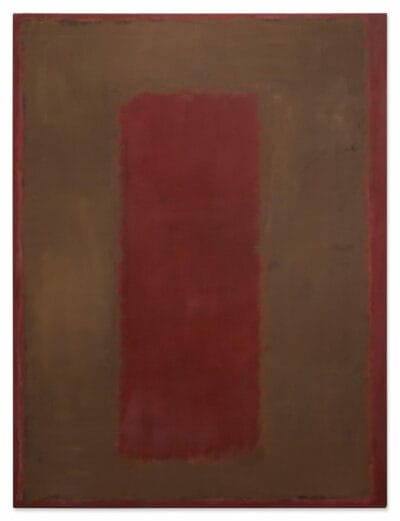

ROTHKO

1958, oil on canvas, 91 ⅞ x 69 ⅛ inches

Estimate on request

In late 1969, Mrs. Fisher Landau visited Mark Rothko’s studio at East 69th Street, just across from her own apartment at Imperial House. Soon after, while she was still pondering the works she had just seen, Rothko died.

But her encounter with the artist’s late work left a deep impression (“My perception of Rothko’s work expanded because of my visit there”, she remembered) and when, some years later, she came to purchase her first work by Rothko, she chose one of the later works that had impressed her so much – a work that relates directly to the famous Seagram Murals, considered by Rothko to be among his greatest achievements.

The majority of works relating to this mythical series now hang in the great museums of the world – in the Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art in Japan, in the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, and in Tate Modern in London, which will be lending all nine of its Seagram paintings to the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris for a major Rothko retrospective this fall. Very few works from this celebrated series, however, remain in private hands. As a result, the appearance of this painting on the market is nothing short of extraordinary: no other painting from the Seagram Mural series has ever appeared at auction before.

In 1950 Rothko visited for the first time Michelangelo’s vestibule in the Laurentian Library in Florence. He was overwhelmed by the intensity of experience and returned to his studio determined to evoke, via his own canvases, that same feeling of complete spiritual immersion. That ambition is fully achieved in this painting, which – not seen in public in over three decades – ranks among the finest of this period ever to appear at auction.

JOHNS

JOHNS Mrs. Fisher Landau met Jasper Johns on numerous occasions in the 1980s and ‘90s, in the course of weekly trips to the galleries and artist studios of SoHo, the Bowery and the East Village. Soon after first meeting Johns in 1985, she began collecting his works.

The dream of the then 24-year-old artist was to set him on a decades-long path which culminates in this masterpiece.

For Johns, the subject itself speaks volumes, pointing to the conflicting poles of deep patriotism and disaffection that existed in America in the mid to late 20th century: a time that saw the McCarthy witch-hunts, the Vietnam war, the Cold War, student protests and so much more. With his famous ‘Flags’ series, Johns taps right into America’s collective consciousness, inviting viewers to consider and connect with, through art, the moment in which they are living.

The power of the subject here, though, is just one aspect of this painting’s appeal and importance. Its form is another. Johns’ paintings emerged at a time when the contemporary art scene was dominated by Abstract Expressionism. Drawing on that, Johns immerses himself in the power of paint. Thick gestural strokes of red, white and blue over a base of orange and green give the painting impressive sculptural depth. At the same time, he puts his own artistic stamp on the Expressionist tradition, re-introducing his own stripped back – and very powerful – form of representation.

Though Johns’ Flags feature in many of the world’s leading institutions for instance at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as in various museums in Europe, only very rarely do they appear at auction. Unique in its doubling and mirroring of the flag, here rendered twice with great detail and rich painterly surface, this painting – an icon of American visual history – is the first of the Flag series to come to auction in almost a decade.

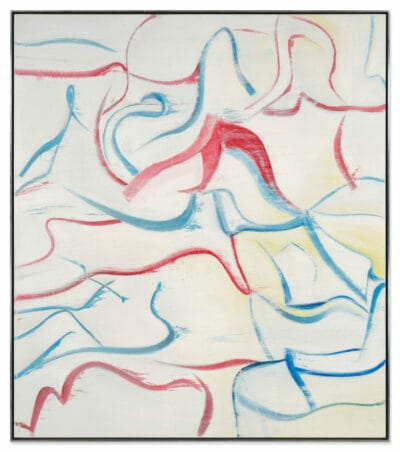

DE KOONING

1983, oil on canvas, 80 x 70 inches

Estimate: $6 – 8 million

Having remained in Emily Fisher Landau’s collection for more than three decades, Untitled XV will make its auction debut this November. Embodying de Kooning’s evolving style of the 1980s, this 1983 painting exemplifies the vibrancy and lyrical abstraction that defined the final decade of the artist’s production. During this pivotal year, de Kooning embarked on a remarkable reinvention, leaving behind the lush, painterly style of his earlier works in favor of a more minimalist approach. Highly acclaimed when first exhibited, his introduction of narrow bands and delicate, fluid lines of vibrant color create the illusion of the canvas twisting and turning in space while subtly hinting at elusive forms.

The critic Robert Storr noted of de Kooning’s paintings of this time, “Of these works, a significant number count among the most remarkable paintings by anyone then active and among the most distinctive, graceful and mysterious de Kooning himself ever made.”

WARHOL

1986, Acrylic and silkscreen on canvas, 80 x 80 inches

Estimate: $15 – 20 million

Andy Warhol’s 1986 Self Portrait was painted just months before his death in February 1987, a poignant reflection on mortality. The final significant body of work that Warhol produced, his 1986 Self Portraits are universally acknowledged as the Pop pioneer’s last great artistic gesture. Wearing the silver wig that had become synonymous with his character, these portraits are more intense and personal than Warhol’s previous self-portraits. The series, including this work, was commissioned by London gallerist Anthony d’Offay for a 1987 exhibition – Warhol’s only gallery show dedicated to self-portraiture. Acquired by Mrs. Fisher Landau in July 1987, Self Portrait is one of just two camouflage self-portraits to appear at auction in the past 15 years.

Measuring 80 by 80 inches, this work is exceeded in scale by only seven known 108-inch examples. Others on this scale hang in leading institutional collections around the world.

RAUSCHENBERG

1962, silkscreen painting, 60 x 60 inches

Estimate on request

Robert Rauschenberg, Sundog

1962, silkscreen painting, 60 x 60 inches

Estimate on request

Executed in late 1962, Sundog marks the beginnings of Rauschenberg’s first experiments with the screen printing process, inspired by a visit to Andy Warhol’s studio in October of that year.

Belonging to a small series of approximately twenty black-and-white silkscreen paintings, of which over half are in museum collections, Sundog was chosen by the artist to feature on the cover of his manifesto, ‘Random Order’, published in Location magazine in the spring of 1963. Sundog has featured in several major exhibitions, including in an important survey of the artist’s work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1990-91.

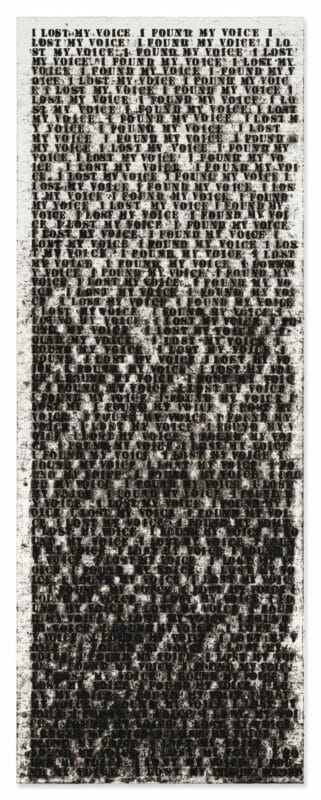

LIGON

1991, Oil stick and gesso on wood panel, 80 x 30 inches

Estimate on request

Over the course of many studio visits in the 1980s and ’90s, Mrs. Fisher Landau developed an ever stronger interest in artists whose practice evokes their experience of the heady yet difficult times in which they were living – a brave and unusual focus for a solo female collector at the time.

Achieving prominence in the early 1990s, Ligon was initially known for his text-based paintings, all of which – deeply rooted in American history, literature and culture – explore themes of identity, race, and language.

Painted just two years after his first solo show, Untitled (I Lost My Voice, I Found My Voice) from 1991 repeats its title to a point where the words are taken into abstraction through repetition. The most important work by the artist to come to auction in nearly a decade, this example belongs to a series of twenty-one ‘door paintings’, all executed on door panels, which – first exhibited at the Whitney Biennial in 1991 – are now widely regarded as Ligon’s most important body of work.

A great admirer of Ligon’s work, Mrs. Fisher Landau acquired this painting just months after it was painted. She also gave several important works by Ligon to the Whitney Museum, an institution central to championing his work, having showcased his paintings in several major exhibitions – Thelma Golden’s groundbreaking “Black Male” show, the 1991 Whitney Biennial, and the seminal 2011 mid-career retrospective in which this work featured.

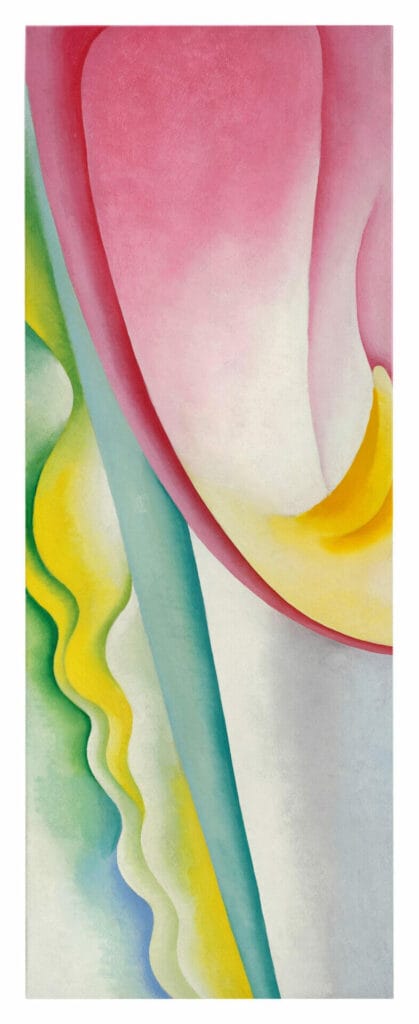

O’KEEFFE

Mrs. Fisher Landau was a longstanding champion and friend of Georgia O’Keeffe, whom she visited regularly in New Mexico, often bringing with her some of the artist’s favorite summer clothes. Over the years, Mrs. Fisher Landau would acquire no fewer than six works by the artist, one of which, Music – Pink and Blue II (1919), she donated to the Whitney Museum in 1991.

Acquired by Mrs. Fisher Landau in 1985, Pink Tulip has been exhibited in many of America’s leading institutions. It also featured in the artist’s landmark 1927 exhibition at the Intimate Gallery in New York – a revered exhibition space for American modernism in the early twentieth century.

One of the things Mrs. Fisher Landau loved most about O’Keeffe was her ability to capture the intrinsic beauty of ordinary subjects by magnifying and abstracting them, evoking a sense of awe and contemplation.

Mrs. Fisher Landau served on the Board of Trustees of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and SITE Santa Fe.

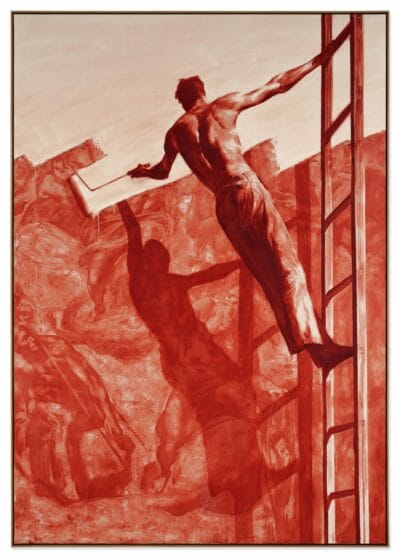

TANSEY

Oil on canvas. 97¼x68¼ inches

Among the artists Mrs. Fisher Landau supported and admired, Mark Tansey was also ‘a dream dinner party guest.’ She bought this painting directly from him.

In this majestic work Tansey depicts a modern painter standing on a ladder and wielding a paint roller across what appears to be Michelangelo’s famous mural, The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. Having already obliterated the heavenly host, the painter’s broad washes are now sweeping across the torso of the commanding figure of Christ, whose upraised hand – the hand with which he saves damns souls – has already disappeared. Like Michelangelo’s image of Christ, the painter on the ladder is a bare-torsoed man of action, vigorously redeeming or condemning with his brush.

With meticulous attention to detail and a rich command of classical painting methods, Tansey breaks through the confines of the canvas, blurring the relationship between representation and reality and at the same time opening up a painterly debate on the question as to whether there is ‘Triumph’ in the suppression of historic and cultural context.

But for Tansey the debate is not academic, it is personal: the painter on the ladder a portrait of himself, grappling with his own status as a contemporary painter wrestling with the history of painting.

The most important work by Mark Tansey to ever come to market – this powerful painting, as arresting to the mind as it is to the eye, featured on the front cover of the defining monograph, “Mark Tansey: Visions and Revisions” by Arthur C. Danto.