Alexander Gray Associates presents recent and historical works by Frank Bowling, Ricardo Brey, Luis Camnitzer,Melvin Edwards, Jennie C. Jones, Steve Locke, Betty Parsons, Joan Semmel,and Hugh Steers. Featuring abstract and figurative paintings, sculptures, and works on paper, the Gallery’s presentations highlight these nine artists’ innovative approaches to materiality, abstraction, and representation.

For several of these artists, the early 1970s denoted a major turning point in their respective practices. Centering a process-driven approach to abstraction, Herbert Spencer Revisited (1974) and other Poured Paintings (1973–78) marked Frank Bowling’s artistic evolution as he moved away from the expressionist gesture of his Map Paintings (1967–71) to investigate the materiality of paint, itself. Works like Herbert Spencer Revisited positioned Bowling at the forefront of contemporary art while articulating the connection between Black identity and abstraction. The fluidity of Bowling’s Poured Paintings is echoed in Melvin Edwards’s works on paper like Texas Blues (1974) whose seemingly spontaneous layered washes of watercolor evoke the same sense of immediacy. Referencing the multiplicity of meaning found in everyday items, Edwards’s 1970s drawings depict the same components—chains and barbed wire—that define his sculptural practice, alluding to both racial oppression and industry.

During the same decade Bowling and Edwards were rearticulating the relationship between identity and abstraction, Joan Semmel also radically reinvented her practice. In 1974, she turned to her own body as the focus of her paintings. With this shift, she transformed her point of view from that of an observer—a viewer outside of the canvas—to that of both an observer and subject. Rendered in a near photorealist style, portraits like Cornered Nipple (1976) from the artist’s Self-Images series (1974–79) capture “the feeling of self, and the experience of oneself.” This experience is amplified in recent works, which directly confront viewers with Semmel’s aging form. In Shameless (2022), the artist presents herself in a frontal seated position to challenge the objectification and fetishization of the female figure, reclaiming her own body as a site of creative autonomy.

Additionally, the 1970s marked a pivotal moment in Luis Camnitzer’s artistic development as he progressed from printmaking to focus on three-dimensional works. In 1973, he began to construct Object Boxes (1973–80) like John and Lillian (1974). Presenting the viewer with an ambiguous relationship between image and text, in this and other related works Camnitzer unpacks the connection between the two, suggesting that the correlation is a spontaneous construct—a changeable narrative meant to be formed by the viewer.

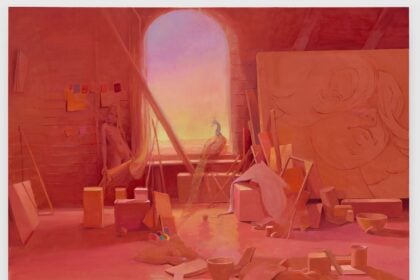

In contrast to this conceptual decoupling of object and language, Betty Parsons championed an emotive, painterly approach to interpret her surroundings. Influenced by the spontaneity and verve of the New York School and the expressive brushwork of Color Field Painting, in abstract canvases like Cousins (1967) she captured what she called the “sheer energy” and “the new spirit” of the natural world. Departing from Parson’s gestural method, Jennie C. Jones’s minimalist compositions employ noise-absorbing materials to explore the perception of sound within the visual arts. Composed of layered felt and acoustic panels, Fluid Red Tone, Bass Clef (2023) encourages viewers to anticipate the presence of sound—as the artist observes, this and other similar paintings are always “active.”

Just as Jones joins multiple components in her practice to reference different discourses and modes of perception, so too does Ricardo Brey. Juxtaposing a myriad of various materials and figurative and abstract imagery, his works on paper and sculptures like Yemaya (2022–23) interrogate the natural world while reflecting his own experience as an Afro-Cuban immigrant to Ghent, Belgium. Similarly personal, Steve Locke’s paintings speak to themes of male desire, vulnerability, and sexuality. Capturing intimate moments between men, Break (2007) and other cruisers paintings emerge as meditations on the gaze, mapping the relationship between identity and desire.

Further conveying the connection between identity and desire, the Gallery’s Kabinett presentation features a selection of works by Hugh Steers painted between 1988–92. These deeply intimate vignettes are connected by their shared imagery of men caring for one another. This care reflects, in part, Steers’s own longing for compassion and love. “It’s as if painting it will make it become real,” Steers once explained. “That painting of a man holding another man is conjuring that tenderness, that hope that someone will still care about you and will be there.” Imbuing soft glances and gestures with elegiac yearning, Steers’s men navigate a world indelibly marked by the isolation, desire, fear, and hope of the AIDS crisis.

Ultimately, the Gallery’s presentations chart an evolving global and political landscape. Responding to inequality and discrimination in contemporary society, these artists’ vibrant compositions articulate and champion new understandings and perspectives, portraying what Steers once characterized as “the humanity of a moment.”