Alexander Gray Associates presents a selection of recent sculptures and works on paper by the interdisciplinary artist Ricardo Brey for Art Basel’s online viewing room. Titled To Sail Forbidden Seas, the Gallery’s digital presentation adapts its name from a 2019 archival box by the artist, I Love to Sail Forbidden Seas and Land in Barbarian Coasts. Part of the ongoing Every Life is a Fire series, the work juxtaposes disparate materials and ideas, literally and metaphorically encapsulating many of Brey’s artistic aims. Referencing the histories and myths of the new and old world—delineating humankind’s origins—this and other pieces by the artist speak to his transnational identity as an Afro-Cuban man who has lived and created art in Belgium for roughly thirty years.

© Ricardo Brey/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Suggesting a history of colonialism—the conquistadors’ conquest of Latin America, for example—I Love to Sail Forbidden Seas and Land in Barbarian Coasts unfurls to reveal a miniature world that culminates in a coronet. Inviting narratives around exploration and exploitation, the lavish box is replete with reflective gold surfaces that recall the looted wealth of Mesoamerica. The work is anchored by a meteorite—barely visible under a tangle of chain and coins—which rests on a stack of folios filled with drawings. A visually cacophonous treasure trove of objects and images, each with their own symbolic meaning, the piece encourages performative engagement from viewers. Designed to be opened and unfolded in a measured, thoughtful way, it charges its mundane components with the near-sacredness of reliquaries. For Brey, however, I Love to Sail Forbidden Seas and Land in Barbarian Coasts is about “the feeling of thinking.” Pointing to the crown, which evokes a missing head, he explains that the ornate display with its countless compartments, sketchbooks, and materials represents the unknowable intricacies of the human mind. After all, as Brey pithily concludes, “The head is a box.”

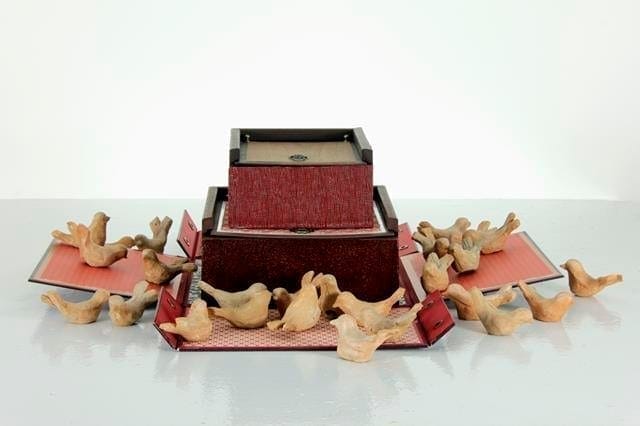

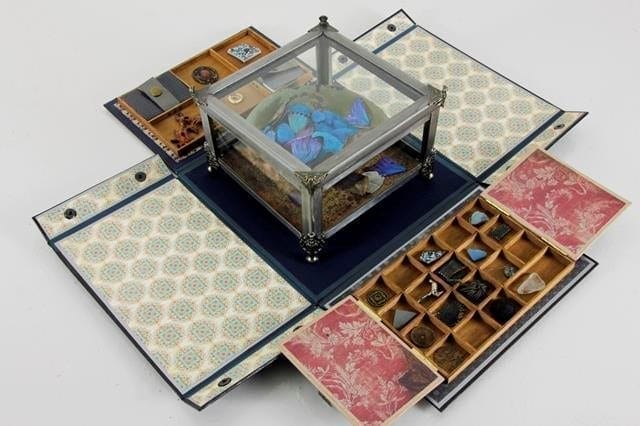

Expanding on this idea, Baño de Polvo (2020) and Admission (2020) also allude to nuanced interior worlds. These two works from Every Life is a Fire transfigure humble items through artistic alchemy into the extraordinary. Baño de Polvo, or “Dust Bath,” boasts a flock of clay birds whose forms are all that remain of a larger 2017 installation, Dust Bathing, which Brey created for the Kathmandu Triennial in Nepal. Like this earlier piece, the box playfully inverts the act of birds rolling in earth by creating them from the very substance they coat themselves in. Also highlighting animals, Admission features Blue Morpho butterflies whose brilliant bodies rest within a glass case. Surrounded by a grid of personal souvenirs collected by the artist over many years, they contribute to a tableau that updates Victorian naturalist displays, which catalogued and preserved observed reality as a way of exerting dominion over it. However, unlike these earlier arrangements, rather than asserting control over nature, Brey’s box relinquishes it. Described by the artist as “[a] shrine to blue,” it creates a reverent, open-ended space for contemplation intended to give “the feeling of hope … and the future.”

Brey echoes the shimmering purity of this shade in recent drawings, which adopt new Parisian and indigo blue palettes. Featuring atmospheric washes of concentrated pigment, these images belong to the artist’s ongoing body of Adrift works, which he began in 2014. Brey originally created this sprawling series in part as a way of processing the immense horror he felt when he returned to his native Cuba after more than twenty years to discover wide-spread deforestation. This shock is made explicit in drawings like Poison Tree (2020), which reflect the artist’s personal concerns about humankind’s harmful relationship with the environment. Meanwhile, Gloves Thistle (2020) builds on other thistle compositions constructed by the artist. Brey identifies with the thistle, which he treats almost as a personal avatar. Incredibly hardy and adaptable, the plant takes root in both the Americas and Europe, flourishing in a plethora of different surroundings and conditions.

Like Brey’s works on paper, his sculptures also draw on a multitude of different references. Light Up (2018) juxtaposes a found bicycle wheel with various decorative round beads, an architectural element, and spherical ornaments made of wood and metal. Partially suspended and threaded through the spokes of the wheel, the varied components symbolically function as planets. Alluding to the vastness of the cosmos, complete with distinct, yet connected celestial bodies, Light Up confirms humanity’s insignificance within the boundless expanse of the universe. Similarly planetary, Weaving hope (2017) consists of a black globe caught in a net of faux jet gemstones. Speaking to Brey’s wishes for the future, the shroud-like meshwork recalls mourning beads, yet is a sign of protection—a talisman against the evil eye.

Always sailing forbidden—or rather uncharted—conceptual seas, Brey’s practice navigates transcultural dialogues to challenge and surmount divisions between myths, religions, and systems of thought and value. Recontextualizing prosaic objects, his works make space for reflections on humanity’s identities and place in the world. As he once wrote, “I refuse to limit my work to a specific subject or to the expression of a specific reality … I create into my work spaces of interaction in which I link elements that at first seem to be opposite but in reality are indissolubly connected: nature/culture, organic/inorganic, western/non-western, my goal is to transmit with my sculptures and installations … this hybrid nature, posing questions rather than answers.”

Ricardo Brey’s work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions, including Adrift at Museum De Domijnen, Sittard, the Netherlands (2019); Fuel to the Fire at the Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen (M HKA), Antwerp, Belgium (2015); BREY at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana, Havana, Cuba (2014); Universe at the Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), Ghent, Belgium (2006–2007); Ricardo Brey, Hanging around at GEM, Museum of Contemporary Art, The Hague, the Netherlands (2004); Galleria Civica, Palazzina dei Giardini, Comune di Modena, Italy (1996); Vereniging voor het Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent, Belgium (1993); and El Origin de las Especies at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana, Havana, Cuba (1981). He has also participated in innumerable group shows, including the 56th Venice Biennale, All the World’s Futures, curated by Okwui Enwezor (2015); Artesur, Collective Fictions at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France (2013); Trattenendosi at the 48th Venice Biennale, Italy (1999); Universalis at the 23rd São Paulo Biennial, Brazil (1996); Documenta IX in Kassel, Germany (1992); and Volumen I at the Centro Internacional de Arte de La Habana, Havana, Cuba (1981). He is the recipient of many awards and grants, including the Prize for Visual Arts from the Flemish Ministry of Culture (1998) and a Guggenheim Fellowship for Sculpture and Installation (1997). Brey’s work is featured in countless private and public collections, including the Bouwfonds Art Collection, The Hague, the Netherlands; Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, Havana, Cuba; CERA Art Collection, Leuven, Belgium; Collection of Pieter and Marieke Sanders, Haarlem, the Netherlands; Collection de la Province de Hainaut, Belgium; de la Cruz Collection, Miami, FL; Fonds national d’art contemporain (FNAC), France; Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection, Miami, FL; Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany; Louis-Dreyfus Family Collection, Mount Kisco, New York; Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana, Havana, Cuba; Museum de Domijnen, Sittard, the Netherlands; Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen (M HKA), Antwerp, Belgium; Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), Ghent, Belgium; Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, Japan, among others