Phillip King and Jeremy Moon first met in 1956 at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where they lived on the same street. Moon was studying law, and King, modern languages. They would remain close friends until Moon’s untimely death in 1973.

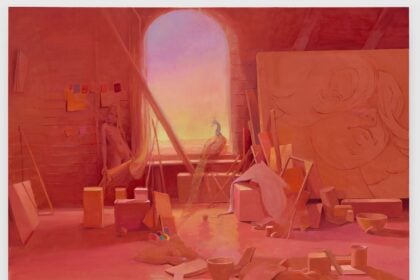

This exhibition will intermix work by both artists throughout Thomas Dane Gallery’s two spaces on Duke Street, St. James’s. Paintings and drawings by Moon from the 1960s and 1970s, as well as a geometric floor-based sculpture from 1972, will sit alongside two large sculptures from the 1960s by Phillip King and a group of hand-made and editioned maquettes made throughout the artist’s career.

The closeness of the artists’ friendship and the influence they would have on one another’s work is clear. Having grown up during the Second World War and experienced the post-war depression, both were keen to reimagine sculpture and painting in new ways. It was in part from America where they took inspiration for this new vision, from Frank Stella and David Smith, but also from the UK, particularly from Anthony Caro. However both felt the remaining vestiges and remnants of the post-war era needed to be cast off, and set about making entirely new forms with innovative, virgin materials that stepped outside of the existing world and into pure abstraction.

While Moon developed a highly rigorous and productive practice as a painter, King developed his language in sculpture. King’s interest was in the fundamentals of objects, their surfaces and volume. He explored how an object stood up, how one part could lean against another to make an intentional object (thus discovering his most recognisable silhouette: the apex or cone). He described his work as the ‘art of the invisible’, referring to the fact that the majority of a sculpture is hidden within its own volume.

Similarly, Moon began exploring the sculptural possibilities of painting, with large, unconventionally shaped canvases, cut-out works (indeed, paintings that are more cut-out than remaining, an idea that resonated strongly with King’s idea of ‘the art of the invisible’) and geometric compositions that were more closely related to objects than traditional works on canvas. He even ventured beyond painting into making actual sculptures, though deliberately avoided any clear distinction between the two.

Moon’s work was heavily inspired by music, particularly jazz, as well as choreography and dance. Repeated patterns of stripes and grids became a way to set up, and then syncopate, rhythm and movement across a surface that subverted the traditional static quality of painting. King too felt this connection with temporality and dance which can most clearly be seen in his Reel series (eg. Dunstable Reel, 1970 and Ring Reel, 2013) and in works such as Green Streamer, 1970, maquettes of which appear in the show.

Key to both artists’ practices was the use of colour and how it related to shape and volume, monochromatically, but more importantly in combination. The relationship between two or more colours became a fundamental building block for both artists. Harmonies and resonances were used to support or undermine the compositional integrity of the works allowing for a strict and formal yet idiosyncratic geometric language.

Artist biographies:

Jeremy Moon (b. 1934, Altrincham, d. 1973, London) received a law degree at Christ’s College, Cambridge in 1957. He worked in advertising and enrolled briefly at Central School of Art, before devoting himself to art in the early 1960s. He taught sculpture at Saint Martin’s School of Art and painting at Chelsea School of Art, while exhibiting extensively within the United Kingdom and internationally. He died in London after a motorcycle accident at the age of 39. The first retrospective of his work took place in 1976 at the Serpentine Gallery in London, and travelled to Manchester City Art Gallery, Manchester; Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge; Ulster Museum, Belfast; and Ikon Gallery, Birmingham. His work is represented in the permanent collections of several international institutions including Tate, London; British Museum, London; Victoria & Albert Museum, London; Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Art Institute of Chicago; Milwaukee Art Museum; Buffalo AKG Art Museum; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; and Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence. In 2022, Luhring Augustine published Jeremy Moon: Starlight Hour, a fully illustrated monograph of the artist’s work which represents the first comprehensive overview of Moon’s life and career.

Phillip King (b. 1934, Tunis, d. 2021, London) was one of the key sculptors of the post-war period. He was an assistant to Henry Moore and a student and then contemporary of Anthony Caro. After graduating he became a key member of the group of young artists who re-imagined sculpture from the 1960s onwards. King’s work was included in the seminal Primary Structures exhibition at Jewish Museum, New York in 1966 (a turning point in contemporary sculpture) alongside Carl Andre, Anthony Caro, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Robert Morris and Robert Smithson. King represented Great Britain at the 1968 Venice Biennale (alongside Bridget Riley) and has also been the subject of ambitious museum survey shows at Whitechapel Gallery, London (1968), Kröller Muller National Museum, Netherlands (1974), Hayward Gallery, London (1981), Le Consortium, Dijon (2013) and Tate Britain, London (2014). King is included in the most illustrious public collections in the world including Tate, London; MoMA, New York; Pompidou, Paris; MOCA, LA; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam and many other national museums worldwide. Many works by King are permanently installed in public places in major cities around the world including London, UK; Munich, Germany; Osaka, Japan and Rotterdam, the Netherlands. King also has works in sculpture parks including Yorkshire Sculpture Park, UK; Kistefos Museet, Norway, Kröller Muller, the Netherlands and Hakone Open Air Museum, Japan. His final public sculpture was unveiled in the French City of Rennes in the spring of 2022.