This March in London, Sotheby’s will offer for sale one of the greatest paintings by Kandinsky ever to come to market. Dating from a transformative moment in Kandinsky’s career, Murnau mit Kirche II (1910) encapsulates the very beginnings of the revolutionary abstract language that would underpin the rest of Kandinsky’s career – and set the next generation of artists on a new path. Executed on an impressive scale, in the near-square format favoured by avant-garde contemporaries from Monet to Klimt, and with a rich palette of contrasting hues, the newly-restituted painting has a remarkable history.

Soon after it was painted, the work was acquired by Johanna Margarete Stern (née Lippmann, 1874–1944) and Siegbert Samuel Stern (1864–1935). Co-founders of a successful textile business, Johanna Margarete and Siegbert were at the heart of the famously glittering cultural life of 1920s Berlin, with a social circle that included Thomas Mann, Franz Kafka and Albert Einstein. Together they built an impressive art collection consisting of well over 100 paintings and drawings, the scope of which reflected their multifaceted tastes and interests, ranging from Dutch Old Masters to much more recent, ground-breaking works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Lovis Corinth, Odilon Redon, Max Liebermann, Edvard Munch and Max Pechstein.

Everything changed, however, following the rise to power of the Nazis: although Siegbert died of natural causes in 1935, Johanna Margarete was eventually forced to flee Germany, in spite of which she still did not escape the Holocaust. In the course of these terrible events, the Sterns’ spectacular art collection was dispersed.

Identified just under ten years ago on the walls of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, where it had been hanging since 1951, Kandinsky’s Murnau mit Kirche II was recently restituted to the descendants of the Stern family. It will now be offered for sale with an estimate in the region of $45 million, with the proceeds to be shared between the thirteen surviving Stern heirs. The sale of the work will also fund further research into the fate of the family’s collection.

Early works by Kandinsky rarely come to the market, with the lion’s share residing in major museum collections across the world. Ahead of its sale in London on 1 March, the painting will be exhibited at Sotheby’s Hong Kong (5-7 February), New York (11-15 February) and London (22 February-1 March).

“Though nothing can undo the wrongs of the past, nor the impact on our family and those who were in hiding – one of whom is still alive – the restitution of this painting that meant so much to our great-grandparents is immensely significant to us, because it is an acknowledgement and partially closes a wound that has remained open over the generations.”

The heirs of Johanna Margarete and Siegbert Stern

“Kandinsky’s Murnau period came to define abstract art for future generations, and the appearance of such an important painting – one of the last of this period and scale remaining in private hands – is a major moment for the market and for collectors. Its restitution after so many years allows us finally to reconnect this remarkable painting with its history, and rediscover the place of the Sterns and their collection in the glittering cultural milieu of 1920s Berlin.”

Helena Newman, Chairman of Sotheby’s Europe and Worldwide Head of Impressionist & Modern Art

“This year marks the 25th anniversary of the conference, held in Washington, D.C., that first established the ground rules for the restitution of art works looted by the Nazis during the Second World War. Since then, Sotheby’s Restitution Department has worked with many heirs and families to reunite them with their stolen property, but the restitution, after so many years, of Kandinsky’s Murnau mit Kirche II to the heirs of Johanna Margarete and Siegbert Stern has been especially resonant and moving, and we are so very glad that the full story will now be told.”

Lucian Simmons, Vice Chairman and Sotheby’s Worldwide Head of Restitution

The Stern Family And Their Collection

Siegbert Stern was a leading entrepreneur and co-founder of the major textiles enterprise Graumann & Stern, head-quartered in a magnificent art nouveau building on Berlin’s Mohrenstrasse.

Surrounded by their splendid collection, Siegbert and his wife Johanna Margarete lived with their four children, Annie, Hilde, Hans and Luise (affectionately referred to as Liesle or Liesel), in a beautiful architect-designed villa in Potsdam / Neubabelsberg, outside Berlin. The family was a close and loving one, as evoked in the many photographs that survive, and in newly-unearthed notes that Siegbert made for his 70th birthday speech.

In addition to their involvement in Berlin’s thriving cultural life, the Sterns were also significant in the Jewish community, and in 1916 helped set up the Jüdisches Volksheim to support Eastern-European Jews living in poverty, an organisation that also served as a source of education and intellectual exchange, with regular visitors including writers and philosophers such as Franz Kafka and Martin Buber.

As the Nazi grip on Germany tightened, the life of the Stern family became increasingly difficult. They were determined to remain in Berlin, but two years after Siegbert’s death in 1935 – as anti-Jewish measures continued to escalate – Johanna Margarete fled, first to Southern Germany, via Switzerland where she visited her brother, and then to the Netherlands. With the help of her son Hans, she was able to retrieve some of her assets, including her furniture and art collection, from Germany.

By 1941, Johanna Margarete, continuing to face persecution as the Nazis occupied Holland, had been declared stateless by the regime. In exchange for the promise of an emigration visa, she handed over a portrait by Henri Fantin-Latour (specially acquired for the purpose, at great cost) to the Dienststelle Mühlmann – an agency set up by the Nazis to acquire works for Germany. The visa never came, and Johanna Margarete was soon forced to sell many of her family’s artworks to survive. She went into hiding in Bussum, near Amsterdam in 1942, but was finally captured and deported to Auschwitz, where she was murdered in May 1944.

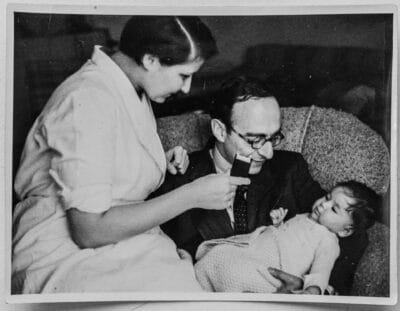

One of the Stern’s daughters, Luise, and her husband, also living in Amsterdam, were similarly taken by the Nazis, deported and murdered. Just before they were arrested, however, they managed to arrange for their seven-year-old daughter Dolly to be taken into hiding by their nanny and her husband – which involved the young child making a terrifying solo journey across occupied Amsterdam on various trams. Dolly spent most of the next two and a half years concealed in a single tiny room, only on rare evenings able to venture cautiously into the rest of the house. The front room of the house was rented out for use by doctors and their patients, and so for the majority of her time there, Dolly was hardly able to move for fear of making any noise that might alert to her presence. Whenever word got round that one of the frequent Nazi searches was imminent, Dolly would hide either in a small, black, spider-infested recess under the floorboards, or behind cleaning materials in the cupboard below the kitchen sink. Throughout this time, all Dolly had for company was a children’s bible and a book of fairytales. The household itself was harsh and loveless, which only amplified Dolly’s mental anguish.

After the war, she emerged a 10-year-old orphan, starting to piece together the fragments of her former life. This was a long and torturous process, made more difficult by the couple who had sheltered her during the war years, who then resisted efforts by her surviving relatives to bring her to live with them in New York.

Following her death in 2014, Dolly’s diaries – recounting in intensely moving detail the unimaginable events and impact of the war years and those that followed – will soon be published by her family. Remarkably, these memoirs are permeated by a sense of how she strove to draw pleasure from the simple, good things in life, and appreciated the beauty of nature all around her. At the same time, Dolly’s utmost inner aim was a stoic one – to die without hatred and to understand in depth the wrongs that she had experienced.

Murnau & The Path To Abstraction

Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter (his lover and fellow artist) visited the Bavarian mountain village of Murnau in the summer of 1908. They quickly fell in love with the place, together purchasing a house there the following year where they spent long happy summers, often with their artist friends Alexei Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin. The village and its surroundings provided a rich repertoire of subjects that were to become central motifs in Kandinsky’s work during these critical years, which saw him take his first steps towards abstraction, heralding a radical change in the narrative of Western art.

In Murnau mit Kirche II, Kandinsky synthesises all the influences he had absorbed during his time in Paris in 1906 to 1907 (Paul Cézanne’s deconstruction of form; the vibrant colour palette of the Fauves, and Vincent van Gogh’s unique landscape idiom), creating something entirely different and absolutely his own: an explosion of colour and form, which – ever more divorced from naturalistic representation – affect the viewer in the emotive and spiritual manner Kandinsky was to articulate, just a year later, in his seminal text, Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

The legacy of definitive works by Kandinsky like Murnau mit Kirche II is clearly distinguished in the art of the Abstract Expressionists working in post-war America, such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, who were indebted to Kandinsky and his pioneering art for taking the first steps on the path to abstraction.