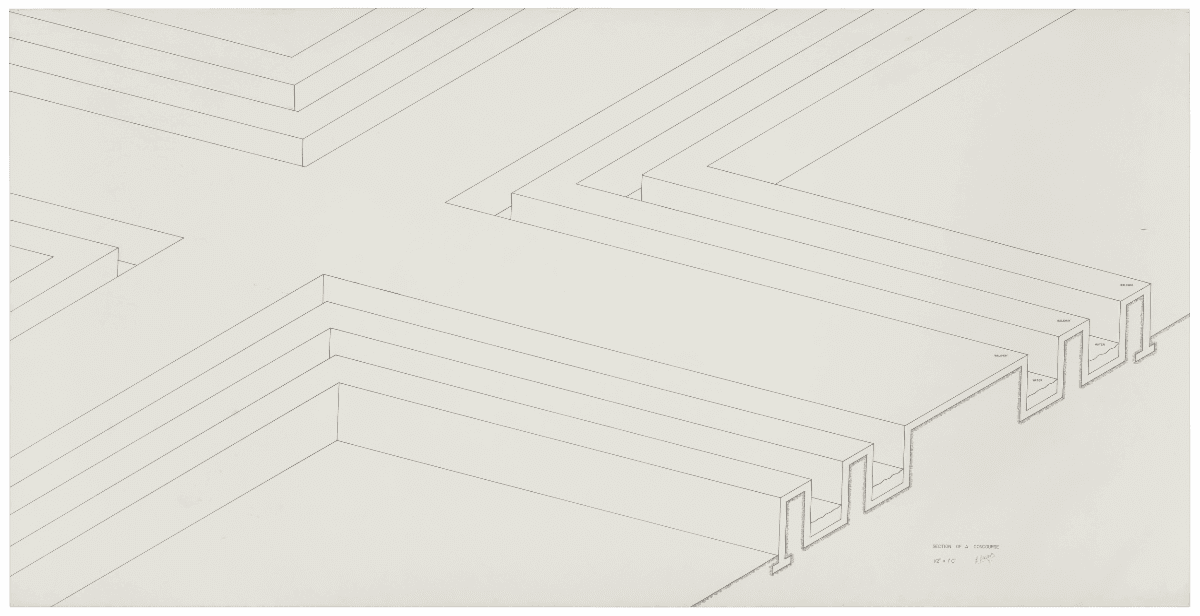

For today’s blog, the gallery invited Sarah Watson, Chief Curator of Hunter College Art Galleries, to write about Robert Morris’ Section of a Concourse, 1971, a drawing she became intimately familiar with while curating the exhibition Robert Morris: Para-Architectural Projects at Hunter College Art Galleries in 2019.

Ink on paper, 42 x 83 inches

© The Estate of Robert Morris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1971, Robert Morris produced some twenty large, ink-on-paper drawings that reveal an expansive imaginary architectural complex. The drawn spaces continue beyond the edges of the paper and appear rendered with the precision of a draftsman, though the artist’s hand remains visible. Writing about this series, Morris posits that the imagined structures were “neither religious nor militaristic”; rather, the “fantasy complex circles around a secular re-entry to time, place and function.”[1] First exhibited in the retrospective of Morris’ work at Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain) in 1971, these drawings echoed the human-scale structures Morris created for the show. In the Tate Gallery press release, the drawings are referred to as the Para-Architectural Projects—observations, exercise courts, aqueducts, courts, concourse, etc., and described as “projects for sculpture on an architectural scale of a type related to Neolithic monuments, ziggurats, fortifications, etc.”

Influenced by Neolithic and Non-Western architecture, Para-Architectural Projects illustrate Morris’ concern with our temporal experience of physical space. He articulates a form of architecture that has a continuous presentness–an open “‘time frame’ or ever-present context”—in which our encounters with space extend beyond a specific moment in linear time.[2] Discussing open architectural forms found in Asia as well as Central and South America, Morris writes:

One’s behavioral response is different, less passive than in the occupation of normal architectural space. The physical act of seeing and experiencing these eccentric structures are more fully a function of the time, and sometimes effort, needed to move through them. Knowledge of their spaces is less visual and more temporal-kinesthetic than for buildings that have clear gestalts as exterior and interior shapes. Anything that is known behaviorally rather than imagistically is more time-bound, more a function of duration than what can be grasped as a static whole.[3]

Included in this series is a rendering for Observatory, a large-scale temporary outdoor project built in Santpoort-Velsen, the Netherlands, as part of the exhibition Sonsbeek 71 (1971). Observatory is the only work from the Para-Architectural Projects realized in situ. Dismantled the year after Sonsbeek 71, Observatory was recreated as a permanent installation in Lelystad, the Netherlands, in 1977. In the Sonsbeek 71 catalogue, Morris argues that the “[Observatory] has a different social intention and aesthetic structure from other art being made at present. I have no term for the work. A kind of ‘para-architectural complex’ would be close but awkward.” The concept, he continues, “derives more from Neolithic and Oriental architectural complexes. Enclosures, courts, ways, sightlines, varying grades, etc., assert that the work provides a physical experience for the mobile human body.”[4]

In large part, Morris’ turn to architecture beyond his temporal and physical location was a response to the repressive social, political, and civic institutions of the 1960s and 1970s—the same hegemonic structures that persist today. In his work that followed the Para-Architectural Projects, Morris directly critiqued these subjects. In 1973, Morris began Labyrinths (1973–74), a series of mechanical drawings and human-scaled installations exploring the labyrinth as a mechanism of control. Originating in ancient Greece, the labyrinth is a complex maze-like environment, wherein its narrow and endlessly winding passageway disorient its navigator. In 1978 Morris produced a series of twelve drawings in a similar vein to the Labyrinth works, titled In the Realm of the Carceral, which interrogates the state’s construction of the individual within the disciplinary space of the prison. Section of a Concourse, included in the Para-Architectural Projects, foreshadows Morris’ preoccupation with the labyrinth. In this drawing, Morris reveals a cross-section of the interior architecture while simultaneously rendering the concourse’s angled pathways as if they extend indefinitely— refusing a delineation between beginning and end.

The Para-Architectural Projects position themselves outside of linear history while prompting us to consider our present architectural frameworks. Melding the prehistoric with the hypothetical, they operate in both the past and future. While titles such as Observatory refer directly to ancient architecture, this series points to a speculative and potentially utopic construction, one that Morris wrote he was “waiting for an enlightened W.P.A.” to build.”[5]

-Sarah Watson, Chief Curator, Hunter College Art Galleries

[1] Robert Morris and Thomas Krens, The Drawings of Robert Morris, exh. cat. (Williamstown, MA: Williams College Museum of Art, 1982).

[2] Robert Morris, “The Present Tense of Space,” in Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, ed. Robert Morris (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1995), 177.

[3] Ibid., 193.

[4] Robert Morris, “Observations on the Observatory” (“Observaties over het Observatorium”), in Sonsbeek 71 (Sonsbeek Buiten De Perken), ed. Geert van Beijeren and Coosje van Kapteyn (Deventer, Netherlands: Drukkerij De IJssel, 1971), part 2, 57.