The George Adams Gallery is pleased to present, Bischoff/Burckhardt: A Dialogue, an exhibition of abstract paintings from 1974-1984 by the influential Bay-Area artist Elmer Bischoff, alongside recent paintings by New York-based painter Tom Burckhardt. These two distinct bodies of work will be installed alongside each other with queues of Burckhardt’s abstracted “portraits” in counterpoint to the monumental scale of Bischoff’s expressive canvases. This will be the first presentation of Bischoff’s late work in New York, since his death in 1991 and the first showing of Burckhardt’s paintings from this series.

Both artists have long toyed with the boundaries between abstraction and figuration – Bischoff famously so when he rejected his successes as an abstract painter to work figuratively in the early 1950s, before returning to abstraction in the 1970s. It is worth noting however, that despite the recognition his figurative work received – deemed “Bay Area Figuration” as envisioned by Bischoff and close friends David Park and Richard Diebenkorn – for the majority of his professional career Bischoff was a more confident and adept abstract painter. Even within the confines of his most lucid figurative paintings, there is a propensity towards the dissolution of form.

Conversely, while Burckhardt has long considered himself an abstract painter, his latest series fully embraces the potential for portraiture within the structure of abstract mark making. The concept of “pareidolia” or the tendency to perceive images within random patterns, is one that Burckhardt has been engaged with for some time and has strongly informed his approach to these paintings. Though not strictly figurative, his “portraits” test the limits of our ability to discern human features. Considerations such as the algorithmic function of facial recognition software have also come into play, resulting in a group of paintings with an uneasy relationship to the signifiers of a face. However, by layering a complex vocabulary of marks and textures, Burckhardt builds up a composition that registers at many levels, allowing the viewer to shift focus between the painting and the image.

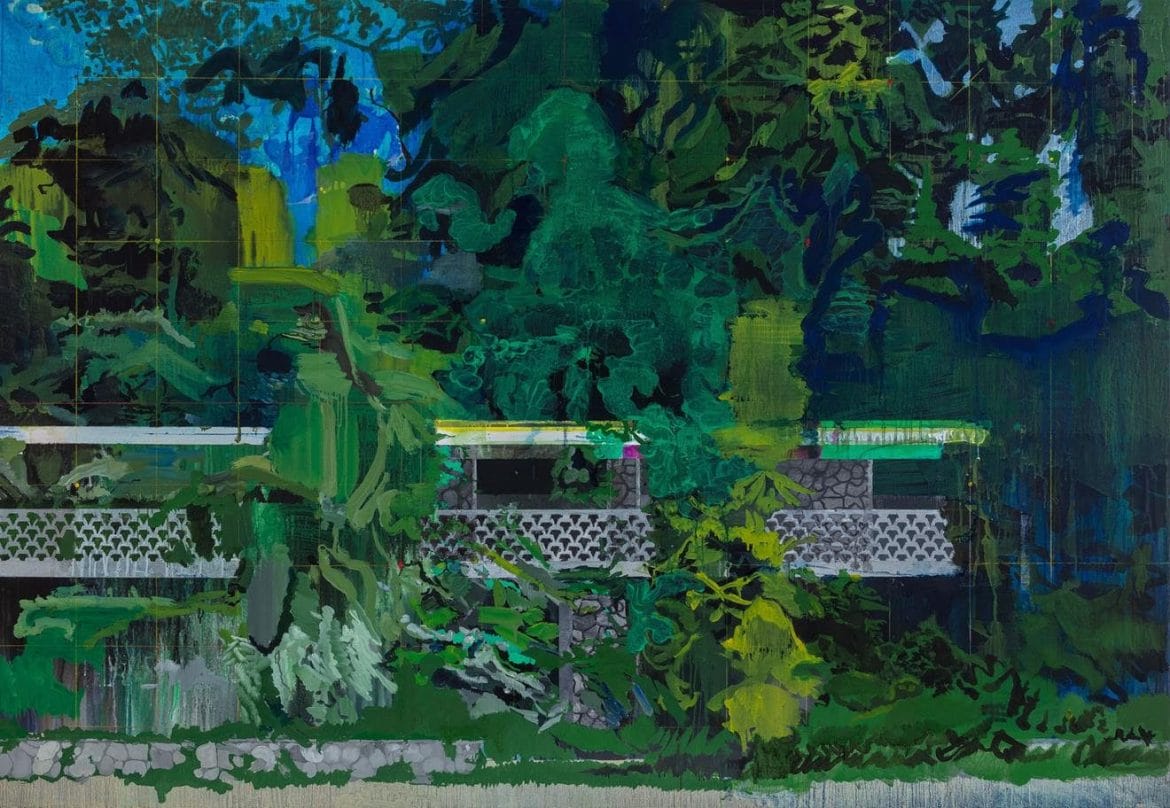

Bischoff’s late abstractions retain references to the observed, whether a still-life or interior or landscape but paradoxically the emphasis is on light: on objects; in an interior; seen through a window, all refracted through a lens of Bischoff’s devising. Compared to his earlier, expressionist mannerisms of the late ‘40s, these paintings are brash and intuitive and most clearly display Bischoff’s musical impulses. The geometric forms, the lines, squiggles and blocks that vibrate through space were memorably described by the artist in 1982 as having “a sort of snap, pop, crack, smash, zip,” while the “in-between area suggests a ‘la la la la la la’.” Motion, sound and color, therefore, become conflated as Bischoff pushes against the boundaries of the capabilities of his medium.

In this sense, there is another point of synergy between the two artists. While the sizes of Burckhardt’s paintings are consistent (all measure at 20 x 16 inches), he begins his process by trimming his stretchers into wavy not-rectangles, a subtle effect that is easy to miss. When seen in a row, as in the exhibition, the irregularities activate the space between each canvas, enforcing the impression of a series of profiles. A reference for Burckhardt when beginning this series was, in fact, observing people waiting in line, a voyeuristic activity that reinforces the visual conundrum his paintings offer. While Bischoff’s compositions do not translate as readily between the abstract and figurative, the paintings he made in the early ‘70s, soon after his break from figuration, provide some context, such as No. 8 (1974). The gridded central motif and organic surrounding forms contain a sense of order; there are suggestions of a window, but any depth of space has carefully been removed. This flattening quickly became the norm for Bischoff – from the mid-70s on his paintings, as seen here, made use of this amorphous space. The edge of Bischoff’s canvases, as for Burckhardt’s, are boundaries as much as delineations, both containing and restraining their contents.