White Cube is pleased to present ‘Bitter Apples’, Julie Curtiss’ first exhibition in Greater China, featuring new paintings, sculptures and works on paper, as well as the artist’s first short film. Curtiss’ unique stylistic language employs crisp outlines and saturated colour, mining a diverse lineage of figuration from 18th- and 19th-century French painting to Japanese woodblock prints and the ‘pop’ imagery of manga and illustration. With an eye for the absurdities of life, she composes scenes replete with playful details and visual puns, infused with a deadpan humour and often erotically charged.

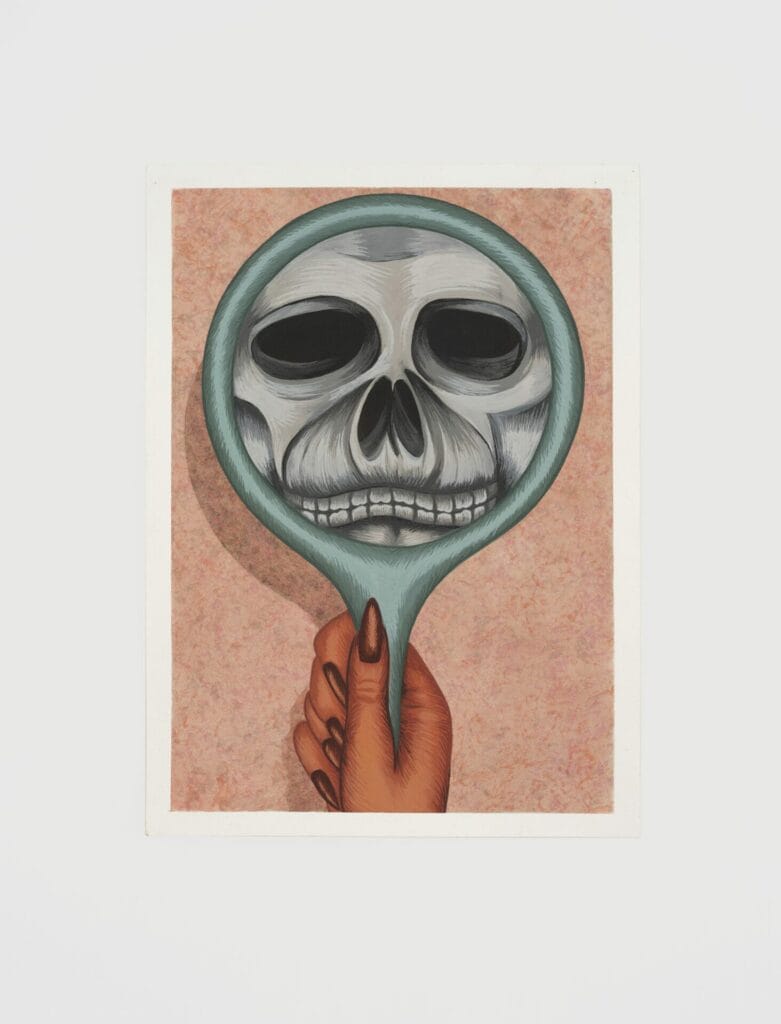

Vanity self portrait

2023

Gouache on paper

31.1 x 22.9 cm | 12 1/4 x 9 in.

© the artist. Photo © White Cube (Kitmin Lee)

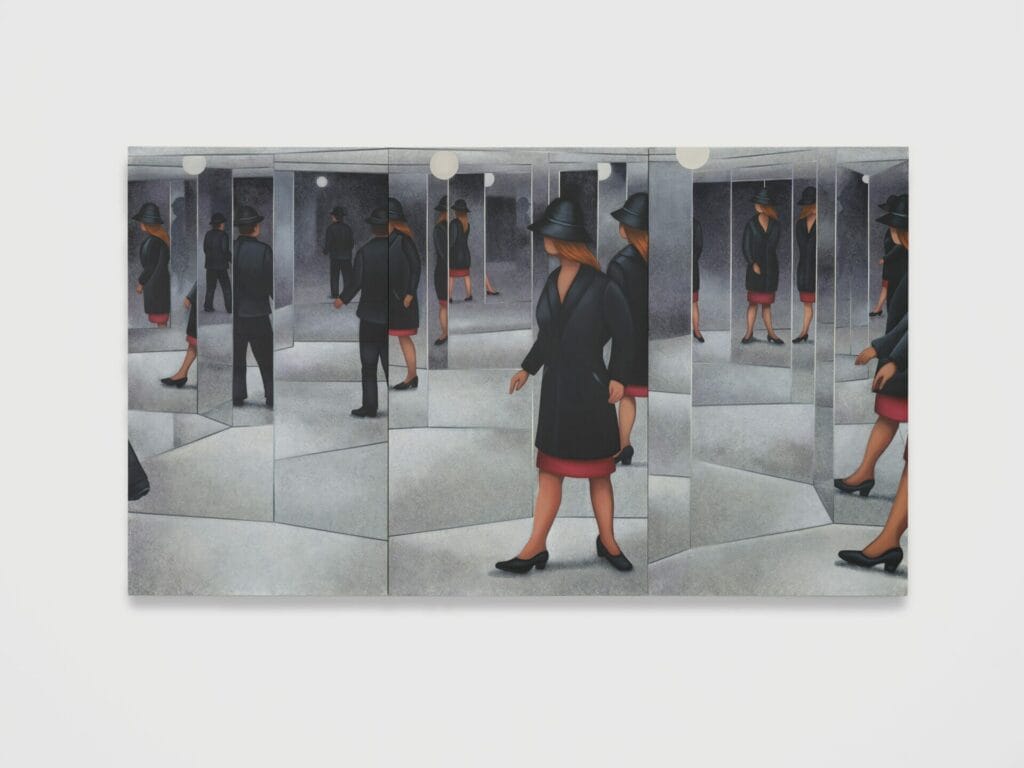

The largest painting in the exhibition, House of Mirrors (2023), based on a still from Charlie Chaplin’s 1928 film, The Circus, replaces the actor with a female figure at the centre of a confounding maze of receding, repeated shadows and reflections. It is fair warning of the games of bafflement and misdirection, tricks of the eye and questioning of reality in which Curtiss loves to indulge, as she does in her titular short film, Bitter Apples (2023). The film functions as a surrealist fable, transporting us into the dreamlike world of her paintings, with sculptures from the gallery exhibition serving as props, and the artist herself taking on an ‘Alice-through-the-Looking-Glass’ role. As she sleeps in a by-the-hour ‘Love Hotel’, wanders through the Tokyo Metro, a cherry blossom orchard, and a kitchen, inanimate objects seem to stir to life around her, and a wildness creeps into the urban order. Influenced by Curtiss’ cinematic heroes Luis Buñuel and Michel Gondry, a closer precursor for Bitter Apples is Maya Deren’s 1943 experimental film Meshes of the Afternoon, which also features its maker as protagonist, and low-tech effects instilling a sense of disquiet and strangeness into everyday settings and objects.

In the artist’s words, ‘[…]at the heart of my interest is how nature and culture relate, the balance between our wild side and our domesticated side. And the weirdness of it all’. Curtiss’ recent relocation to Florida has provided fertile ground for the artist, influencing a further series of works in which lush foliage and tropical birds intrude on domesticity. It is a depiction of nature which is perhaps appropriately ‘Floridian’: not lacking in genuine threat, but containing an element of artificiality. The potted palms are as crisply theatrical as the jungle imagined by Henri Rousseau, but the lurking alligators appear real; the carpet of grass is perhaps actually a carpet, except that here it has a golf hole and there a watering hole. This synthetic paradise, and perhaps also the prospect of impending parenthood, brought art-historical depictions of Paradise and of the Garden of Eden to the artist’s mind. One in particular was Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) with its portrayal of naked figures and animals at play together, while Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432) fascinated her for its depiction of Adam and Eve in its outer panels; convincingly real portraits of imperfect bodies, both symbolic and very particular.

The Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible recounts the story of the first man and woman’s loss of innocence, their discovery of shame and their expulsion from Eden after Eve succumbs to the serpent’s temptation and shares the forbidden fruit with Adam. The tale

Steamy mussels

2023

Acrylic and oil on canvas

Diameter: 50.8 cm | 20 in.

© the artist. Photo © White Cube (Kitmin Lee)

appeals to so many of the artist’s preoccupations: temptation, seduction, deception, even gender dynamics. In Serpent (2023) she infuses these themes with an incongruous domesticity, in which we see the entwined legs of the first couple in a plush interior, appearing to have been consumed by the eponymous creature, while the offending apple, and the source of temptation, rests as a core on the nightstand. In South of Eden (2023) – whose title suggests events following their expulsion from the garden – Adam and Eve are depicted companionably brushing their teeth at a bathroom mirror set under the loggia out of a Renaissance annunciation. The tan lines from a modern bikini hint at the part of the tale where Eve covers herself for the first time in her newfound shame, serving to make her as convincingly specific as van Eyck’s couple.

Weaving Adam and Eve’s story into wider themes of masculinity and femininity, Curtiss playfully stages the battle of the sexes in Stepping Toes (2022), and in two versions of Duel (both 2022), where cartoonish and non-threatening genitalia engage in a face off, suspender belt arrayed against a pistol holster. In one of a pair of portraits in profile, The Non-existent Knight (2023) sports an anachronistic business suit under his helmet, and though the visor is down, we recall that in Italo Calvino’s novel of the same title, the titular knight proves to be an empty suit of armour that fulfils the roles and expectations of chivalric code. Curtiss gives him a similarly faceless counterpart, the lady Nautilus (2023), whose elaborate coiled hairstyle mimics the sea creature’s shell and sensitive tentacles. It is impossible not to supply a psychological reading of the armoured yet imprisoned male and the flexible, sensory female. In fact, the feminine elements of Curtiss’ works are often combined with the animal in what could be described as intimate terms that play on contrasting sensory texture: a fish in a gauzy bra, lovebirds nesting in an ear curtained by hair, or a sly duck sitting for a portrait as accessory to a formal 19th-century costume.

The biblical framework raises questions of sin and temptation, lust and innocence, but Curtiss refuses judgment and exacts no price for pleasure. There is a prelapsarian playfulness in the sensuous frolics of women and assorted creatures, but nothing innocent in the deadpan innuendo of Rude Clam, Steamy Mussels or Smoking Gun (all 2022). Sex, she seems to suggest, is part of life and death, of the duel of seduction and the start of parenthood. She baffles us with mirrors, teases us with unconvincing UFOs and biblical fables, but what Curtiss seems to proffer as trustworthy is the solidity of flesh and the reality of our earthly delights.

House of mirrors

2023

Acrylic and oil on canvas

Overall: 152.4 x 266.7 cm | 60 x 105 in

3 parts, each: 152.4 x 88.9 cm | 60 x 35 in.

© the artist. Photo © White Cube (Kitmin Lee)

Born and raised in Paris, Curtiss studied at l’Ėcole des Beaux-Arts before moving first to Japan and then to New York, now working between Brooklyn, New York and St Petersburg, Florida. Recent solo exhibitions include Anton Kern Gallery, New York (2022); White Cube Mason’s Yard, London (2021); Various Small Fires, Los Angeles, California (2018); and 106 Green, Brooklyn, New York (2017). Group exhibitions include Dallas Museum of Art, Texas (2023); Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois (2023); Yuz Museum, Shanghai, China (2023); FLAG Art Foundation, New York (2023); Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul (2022); Biennale des Arts de Nice, France (2022); and The Shed, New York (2021). She has been the recipient of a number of fellowships and awards, including Youkobo Art Space Returnee Residency Program, Tokyo (2019); Fellow of the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program, New York (2018); Saltonstall Arts Colony Residency, New York (2017); Contemporary Art Center at Woodside Residency Program, New York (2013); VAN LIER Fellowship, New York (2012); Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy’s Young Artists Award (2004); and Erasmus European Exchange Program Grant, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Dresden, Germany (2003).

Curtiss’ work is represented in a number of museum collections, among which are Bronx Museum, New York; Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio; Dallas Museum of Art, Texas; High Museum, Atlanta, Georgia; LACMA, Los Angeles, California; Maki Collection, Japan; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Yuz Museum, Shanghai, China.